Electrolytes are minerals in your body and blood that affect how your body functions, particularly during exercise. When you sweat, you lose electrolytes. And, as anyone who’s ever tasted their own sweat during a hard workout knows, sweat is salty. That’s because the primary electrolyte you lose when you sweat is sodium.

Why are electrolytes important and why is it so important to replenish them?

Replenishing electrolytes during exercise helps maintain plasma volume, which is depleted when you sweat. Hydration Drinks with electrolytes help maintain plasma volume over time better than water alone (Anastasiou, 2009). This is important because maintaining plasma volume will prevent decreases in performance associated with dehydration. Endurance athletes can suffer from reduced power related to dehydration as much as from fuel depletion. Exercise performance is impaired when athletes dehydrate by as little as 2% body weight. Losses of more than 5% of body weight decrease ability to perform by as much as 30%. (Armstrong et al. 1985; Craig and Cummings 1966; Maughan 1991; Sawka and Pandolf 1990).

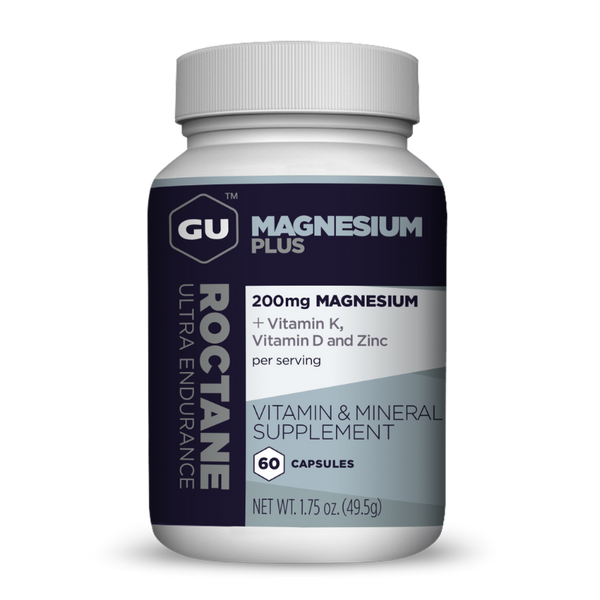

Another reason to replace electrolytes during exercise is to help prevent hyponatremia from over-ingestion of fluids during exercise (Anastasiou, 2009, Twerenbold, 2003). Consuming electrolytes in a concentrated form such as in an Energy Gel or Roctane Electrolyte Capsule will be most effective at combatting hyponatremia. This is because intake of sports drinks alone can lead to hyponatremia since salt concentrations are more diluted than the blood.

Consuming electrolytes, specifically sodium, may help prevent cramping in some individuals during exercise. Several factors cause exercise induced muscle cramping, including fatigue and neuromuscular factors associated with increasing exercise stress too quickly. However, while not universally observed (Seltzer, 2005) research has shown that individuals who are prone to cramping tend to lose more salt in their sweat compared to athletes who do not cramp (Stofan, 2005), and salt replacement interventions have been successful at preventing cramping in some athletes (Bergeron, 2003).

How do I know how much I’m losing?

Sweat rates and sweat sodium concentration are quite variable between individuals (Valentine 2007). As a result, athletes need to experiment with both water and electrolyte intake during exercise to see what works for them in different environments like the heat of summer and the cold of winter.

The environment also plays a role in the amount of electrolytes lost during exercise. We lose greater amounts of electrolytes in the summer heat. The addition of humidity presents an extra heat stress on the body because off decreased evaporative cooling, which make you sweat more to compensate and leads to more electrolyte losses. However, thermal loads can also be high in the winter and should not be overlooked.

How do I best replace them?

Electrolytes can be consumed in many different forms during exercise. Most think about an electrolyte drink, but electrolytes are also found in many sports products and foods. Since sodium is co-transported in the gut with glucose and amino acids, there are benefits to consuming sodium with other calories. Most other electrolytes are absorbed passively.

What’s the Bottom Line?

So how much sodium should athletes consume during exercise? This will vary from athlete to athlete, and be based on environmental factors like heat, so experiment in training to dial in what works best for you. As a starting point, try consuming 300-800 mg of sodium per hour.

References

- Almond CS, Shin AY, Fortescue EB, Mannix RC, Wypij D, Binstadt BA, Duncan CN, Olson DP, Salerno AE, Newburger JW, and Greenes DS. Hyponatremia among runners in the Boston Marathon. The New England journal of medicine 352: 1550-1556, 2005.

- Casa DJ, Stearns RL, Lopez RM, Ganio MS, McDermott BP, Walker Yeargin S, Yamamoto LM, Mazerolle SM, Roti MW, Armstrong LE, and Maresh CM. Influence of hydration on physiological function and performance during trail running in the heat. J Athl Train 45: 147-156, 2010.

- Daries HN, Noakes TD, and Dennis SC. Effect of fluid intake volume on 2-h running performances in a 25 degrees C environment. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 32: 1783-1789, 2000.

- Ebert TR, Martin DT, Bullock N, Mujika I, Quod MJ, Farthing LA, Burke LM, and Withers RT. Influence of hydration status on thermoregulation and cycling hill climbing. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 39: 323-329, 2007.

- Frizzell RT, Lang GH, Lowance DC, and Lathan SR. Hyponatremia and ultramarathon running. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 255: 772-774, 1986.

- Goulet ED, Rousseau SF, Lamboley CR, Plante GE, and Dionne IJ. Pre-exercise hyperhydration delays dehydration and improves endurance capacity during 2 h of cycling in a temperate climate. J Physiol Anthropol 27: 263-271, 2008.

- Noakes TD, Goodwin N, Rayner BL, Branken T, and Taylor RK. Water intoxication: a possible complication during endurance exercise. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 17: 370-375, 1985.

- Rodriguez NR, Di Marco NM, and Langley S. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Nutrition and athletic performance. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 41: 709-731, 2009.

- Sawka MN, Burke LM, Eichner ER, Maughan RJ, Montain SJ, and Stachenfeld NS. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 39: 377-390, 2007.

- Siegel AJ, d’Hemecourt P, Adner MM, Shirey T, Brown JL, and Lewandrowski KB. Exertional dysnatremia in collapsed marathon runners: a critical role for point-of-care testing to guide appropriate therapy. Am J Clin Pathol 132: 336-340, 2009.